Friends, I’m embarking on a bit of an insane undertaking, but one that I feel is important: I am going to attempt to make an exhaustive list of all pagan movies in Western film.

Why film? Well, a book list would be too long, but at the same time, perhaps too easy. I hold an undergraduate degree in English and a Master of Fine Arts in creative writing. Stories, and the analysis of stories, fascinate me. And while I consider myself to be quite adept at creating and analyzing those little black and white arrangements of letters on a page, film—photography, moviemaking, the bending of light and the capturing of sound to immerse a watcher into a completely different world is beyond me. While I couldn’t tell you at all how to go about making one, let alone a good one, I am a deep admirer and appreciator of movies.

Where do we begin? And what constitutes a “pagan film?” While some film’s existence on this list might be self-evident (Valhalla Rising, Gladiator, Troy) my other choices might make significantly less sense. There might be many films on this list which the reader will disagree with. Some of these might be considered a stretch. However, this list is not so much a way to present ideologically pure European pagan films (if that was the case, this list would be very short and pointless); but rather, to illustrate just how much of the spirit of pagan creation, pagan and pre-Abrahamic morality, and depictions of our deities, spirits and our mythic creatures, permeate through Western art, even in unlooked for places. This is a list I made for myself, as much as anyone else. There are many scattered all around the world, hopeless, lost in a post-Abrahamic and post-Industrial culture, looking for their old gods and ancestors, perhaps not realizing that they and many others who weave into the worldbending tapestry of Western art, carried them all along.

I decided to include films that had at least one or more of these classifications:

Takes place in a real historical setting in pre-Christian or pre-Islamic Europe, the main cast of characters are all, or nearly all, worshippers of their own various ancestral traditions (i.e. Gladiator, Troy, The Northman). Film is not informed by Christian morality, the characters do not have a Christian conversion (This why, for example, any iteration of Ben-Hur will not be included).

Takes place in a non-Christian or not explicitly Christian fantasy setting that resembles medieval/Renaissance Europe (or any time period in Europe). Has fantastical or mythological elements that could reasonably be traced to a pagan origin (i.e., Conan the Barbarian, The Lord of the Rings Trilogy, various animated Disney movies).

Takes place in Christianized Europe, North America, Australia, South Africa, or South America and centers on those of European descent, but contains pagan elements (this can include elements that are fantastic or mythological, i.e., the various versions of the King Arthur story, or any story in American film that features legendary, larger-than-life figures like Paul Bunyan).

Does not take place in pagan Europe or a fantastical equivalent, may take place in Christianized Europe, North America, Australia, South Africa, or South America, centers on those of European descent and includes positive depictions of greatness, ingenuity, or physical strength by Europeans and their Diaspora, or teaches a moral lesson that is explicitly European, or contains elements of fated tragedy that is European (i.e., iterations of Macbeth) This moral lesson might be Christian on its face, but can be reasonably traced back to ancestral belief.

Note 1: While there are many fascinating examples of ancestral belief and regional mythology depicted in movies by Asian/Indian, African, Middle-Eastern, and Native American filmmakers, I will not be including them in this list, as that would make it frighteningly long and unwieldy.

Note 2: The history of photography and film is vast and fascinating, but it is not my area of expertise. I will not really go into any sort of lengthy discussion regarding the changes in film for decade to decade, the updated cameras, the invention of new special effects, the boom of sounds and splash of color that appear on screens, replacing the silent black and white forever.

Note 3: For every decade, I will pick a few films to highlight and discuss. For the rest, I’ll only provide a very brief summary.

Without further ado:

The 1800s:

The 1800s saw the great leap from still photography, to moving projections, to actual running life captured on film, albeit silent, and in shades of gray—a far cry from the color-soaked, CGI-scapes of today. This first installment will just be a short little introduction to what I hope will grow into a long, wonderful list that is able to be referenced by any looking to find aspects of ancestral religion in the moving art form.

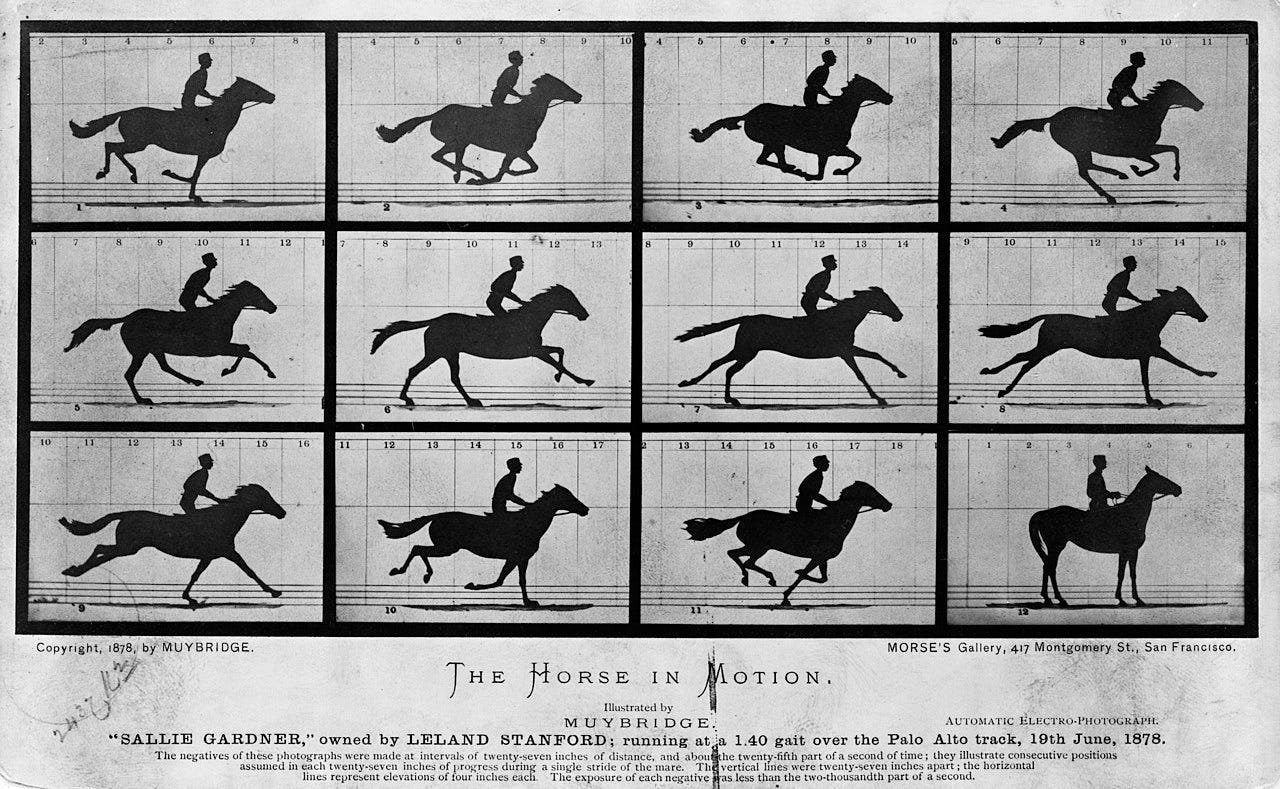

Highlight: The Horse in Motion (England, 1870) - What was the very first film to ever be in the world? This is hotly debated, but many believe it to be The Horse in Motion—a series of cards by English photographer Eadweard Muybridge, depicting the various gaits of several horses. Muybridge, in addition to creating the card series, also conceived the device on which they were viewed. The zoopraxiscope, and the cards that it projected, were not the firsts of their kind, but they represented a great leap in studying pictures in motion, particularly the gaits of animals. And really, what more deeply Indo-European image could be fitting for the world's first movie, but the inexorable movement of a horse, on which the lives and fates of so many before us have been stamped? As for Muybridge—well, to put it simply, he had a life fit for a movie.

Born Edward James Muggeridge in Kingston upon Thames in 1830, Muybridge shed his birth names and delved back into the past to take the older, Anglo-Saxon forms, which, with his wild hair and beard, his bright eyes, keen, searching for light and motion, he wore well. The highlights of Muybridge’s life are many, but some that truly delighted me to read about include his photography taken in the American West, surviving a violent stagecoach crash that left him in a coma for nine long nights and also gave him a head full of shocking, premature white hair, his film pioneering and motion studies, the conversion of a two-wheel carriage into a moving photography studio dubbed Helios’ Flying Studio, and the point-blank execution of his much younger wife’s lover. I say!

Men Boxing (U.S.A, 1891) - A short depicting two Edison employees sparring.

Blacksmithing Scene (U.S.A, 1893) - A short depicting blacksmiths at work, shot by William K.L Dickdon under the direction of Thomas Edison,

La Fée aux Chou (Eng. The Fairy of the Cabbages, France, 1896) - This film has the distinction of being the first ever first female-directed film.

The Boxing Kangaroo (England, 1896) - When I asked a group of all pagan men if this film should be included, I was told “Depiction of valor. Yes,” and “Man fighting against a fell beast? Yes,” and “Dude, this rules.” So I suppose that settles it.

Kørsel med grønlandske hunde (Eng. Driving with Greenland Dogs, Denmark, 1897) - The first Danish moving film.

Old Man Drinking a Glass of Beer (England, 1897) - No elaboration needed.

La Lune à un mètre (Eng. The Astronomer’s Dream, France, 1897) - an astronomer has a strange, lunar dream…

The Pillar of Fire (U.S.A, England 1898) - A short based on H. Rider Haggard’s She.

Cendrillon (Eng. Cinderella, France, 1899) - This is very first time (as far as I can tell) that the Cinderella fairytale was adapted to film.

Next up, the 1900’s (1900-1909) which will be quite a bit longer. I am always open to film suggestions (particularly from countries outside of the Anglosphere, which will be the places I know the least about) or any constructive modifications on my criteria for “pagan film.”

- Huwila